The outbreak of the Kosciuszko Insurrection was a last-ditch attempt to save the Rzeczpospolita that had been plundered by the partitioners and sold out by the Targowiczans. Kosciuszko, as a good commander, realized that he could only succeed in his fight against the Russians through rapid action, aiming to capture as much Polish territory as possible from which military enlistment would then take place. All this had to happen before the Russian Czar would send in his troops to crush the rebellion. Kosciuszko therefore set off at the head of 1,000 soldiers from Krakow to Warsaw. The detachment was supported by a Krakow militia consisting of peasants equipped with scythes set on stakes. The Kosynierzy even became a symbol of the uprising in a short time.

About 40 kilometers from Krakow, Kosynierzy’s path was replaced by a detachment under the command of Major General Alexander Tormasov, numbering about 3,000 soldiers. The Russians disregarded the Poles, not waiting for the rest of the troops commanded by Gen. Denisov. The Russians attacked by striking in the center and on the left wing of the Polish troops. Victory was close, especially after an impressive cavalry charge with momentum. The increased pressure on the left wing, however, Kosciuszko intended to take advantage, launching a counterattack in the center. The decisive strike against the Russian artillery was then carried out by the Kosciuszko soldiers, who passed into legend. Supported on both wings by units of regular infantry. The attacking Kosyniers were not stopped by two salvos from cartridges, and after a short battle the Russian battery was captured and the Russian soldiers were felled. Bartosz Glowacki particularly distinguished himself in the battle, being the first to reach the Russian cannons and to cover the burning fuse with his cap, for which he was ennobled by the Supreme Commander after the battle. Despite this victory, the Russians achieved that they would not allow Kosciuszko’s troops to reach Warsaw. However, upon hearing of the Polish victory, uprisings broke out in both Warsaw and Vilnius. Kosciuszko returned to Krakow to present the townspeople with captured Russian cannons and recruit more soldiers.

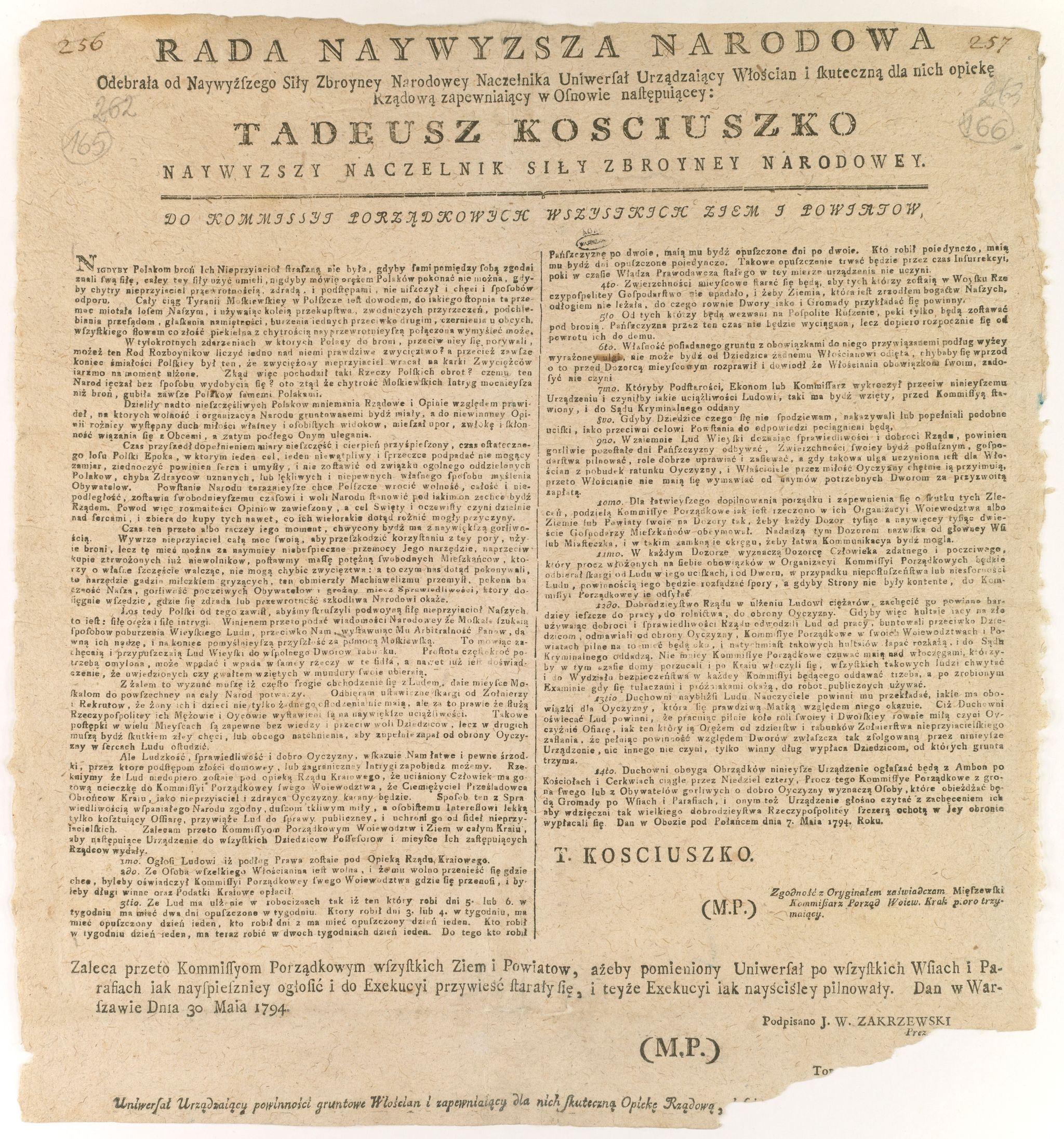

The Russian army had not been driven from all of Lesser Poland and began to draw towards Krakow. Wanting to avoid breaking up his army, Kosciuszko set up a fortified camp near Połaniec in the forks of the Vistula and Czarna rivers. It was in Połaniec that, wishing to mobilize more peasants to engage in battle, he issued the Polaniec Uniwersal. The provisions of the Uniwersal included: limiting the serfdom of the peasants, granting them personal freedom, granting them the right to leave the land, recognizing the limited right of the peasants to pursue their cases in the courts, ensuring non-removal from the land, prohibiting rugby and confirming subordinate property, reducing serfdom from 1/3 to 1/2, with the promise of further relief after winning the uprising, suspending the execution of serfdom to peasants called up to the army, and introducing the office of the caretaker, who was the first government official in the history of Poland to represent peasant affairs. One caretaker was to have under his care a district of about 1,000 farms. He was to take care of compliance with the provisions of the Uniwersal.

With this document Kosciuszko guaranteed himself a supply of fresh recruits. On the site of the issuance of the universal on the 100th anniversary of Kosciuszko’s death, a mound bearing his name was erected. The Universal itself lost its power after the defeat of the uprising. However, it was an important element in drawing the entire society into the fight for the Fatherland.

Author: Krzysztof Drozdowski